This post describes the complete HTTP protocol how it works.

HTTP stands for Hypertext Transfer Protocol. It’s the network protocol used to deliver virtually all files and other data (collectively called resources) on the World Wide Web, whether they’re HTML files, image files, query results, or anything else. Usually, HTTP takes place through TCP/IP sockets.

A browser is an HTTP client because it sends requests to an HTTP server (Web server), which then sends responses back to the client. The standard (and default) port for HTTP servers to listen on is 80, though they can use any port.

HTTP is used to transmit resources, not just files. A resource is some chunk of information that can be identified by a URL (it’s the R in URL). The most common kind of resource is a file, but a resource may also be a dynamically-generated query result, the output of a .aspx file, a document that is available in several languages, or something else.

Structure of HTTP Transactions:

Like most network protocols, HTTP uses the client-server model: An HTTP client opens a connection and sends a request message to an HTTP server; the server then returns a response message, usually containing the resource that was requested. Once the connection is opened It remains open in order to process further requests.

The format of the request and response messages is similar, and English-oriented. Both kinds of messages consist of:

- an initial line,

- zero or more header lines,

- a blank line (i.e. a CRLF – new line by itself), and

- an optional message body (e.g. a file, or query data, or query output).

Put another way, the format of an HTTP message is:

Header1: value1

Header2: value2

Header3: value3

it can be many lines long, or even binary data $&*%@!^$@>

Initial lines and headers should end in CRLF, though you should gracefully handle lines ending in just LF. (More exactly, CR and LF here mean ASCII values 13 and 10, even though some platforms may use different characters.)

Initial Request Line:

The initial line is different for the request than for the response. A request line has three parts, separated by spaces: a method name, the local path of the requested resource, and the version of HTTP being used. A typical request line is:

GET /path/to/file/index.html HTTP/1.0

Notes:

- GET is the most common HTTP method; it says “give me this resource”. Other methods include POST and HEAD. Method names are always uppercase.

- The path is the part of the URL after the host name, also called the request URI (a URI is like a URL, but more general).

- The HTTP version always takes the form “HTTP/x.x“, uppercase.

Initial Response Line (Status Line):

The initial response line, called the status line, also has three parts separated by spaces: the HTTP version, a response status code that gives the result of the request, and an English reason phrase describing the status code. Typical status lines are:

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

or

HTTP/1.0 404 Not Found

Notes:

- The HTTP version is in the same format as in the request line, “HTTP/x.x“.

- The status code is meant to be computer-readable; the reason phrase is meant to be human-readable, and may vary.

- The status code is a three-digit integer, and the first digit identifies the general category of response:

- 1xx indicates an informational message only

- 2xx indicates success of some kind

- 3xx redirects the client to another URL

- 4xx indicates an error on the client’s part

- 5xx indicates an error on the server’s part

The most common status codes are:

200 OK

The request succeeded, and the resulting resource (e.g. file or script output) is returned in the message body.

404 Not Found. The requested resource doesn’t exist.

301 Moved Permanently

302 Moved Temporarily

303 See Other (HTTP 1.1 only)

The resource has moved to another URL (given by the Location: response header), and should be automatically retrieved by the client. This is often used by a CGI script to redirect the browser to an existing file.

500 Server Error

An unexpected server error. The most common cause is a server-side script that has bad syntax, fails, or otherwise can’t run correctly.

Header Lines:

Header lines provide information about the request or response, or about the object sent in the message body.

The header lines are in the usual text header format, which is: one line per header, of the form “Header-Name: value“, ending with CRLF. . Details about RFC 822 header lines:

- As noted above, they should end in CRLF, but you should handle LF correctly.

- The header name is not case-sensitive (though the value may be).

- Any number of spaces or tabs may be between the “:” and the value.

- Header lines beginning with space or tab are actually part of the previous header line, folded into multiple lines for easy reading.

Thus, the following two headers are equivalent:

Header1: some-long-value-1a, some-long-value-1b

HEADER1: some-long-value-1a,

some-long-value-1b

HTTP 1.0 defines 16 headers, though none are required. HTTP 1.1 defines 46 headers, and one (Host:) is required in requests. For Net-politeness, consider including these headers in your requests:

- The From: header gives the email address of whoever’s making the request, or running the program doing so. (This must be user-configurable, for privacy concerns.)

- The User-Agent: header identifies the program that’s making the request, in the form “Program-name/x.xx“, where x.xx is the (mostly) alphanumeric version of the program. For example, Netscape 3.0 sends the header “User-agent: Mozilla/3.0Gold“.

These headers help webmasters troubleshoot problems. They also reveal information about the user. When you decide which headers to include, you must balance the webmasters’ logging needs against your users’ needs for privacy.

If you’re writing servers, consider including these headers in your responses:

- The Server: header is analogous to the User-Agent: header: it identifies the server software in the form “Program-name/x.xx“. For example, one beta version of Apache’s server returns “Server: Apache/1.2b3-dev“.

- The Last-Modified: header gives the modification date of the resource that’s being returned. It’s used in caching and other bandwidth-saving activities. Use Greenwich Mean Time, in the format

- Last-Modified: Fri, 31 Dec 1999 23:59:59 GMT

The Message Body:

An HTTP message may have a body of data sent after the header lines. In a response, this is where the requested resource is returned to the client (the most common use of the message body), or perhaps explanatory text if there’s an error. In a request, this is where user-entered data or uploaded files are sent to the server.

If an HTTP message includes a body, there are usually header lines in the message that describe the body. In particular,

- The Content-Type: header gives the MIME-type of the data in the body, such as text/html or image/gif.

- The Content-Length: header gives the number of bytes in the body.

Methods:

GET :

The GET method is used when the client wants to retrieve a document from the server.

POST:

A POST request is used to send data to the server to be processed in some way, like by an aspx file. A POST request is different from a GET request in the following ways:

- There’s a block of data sent with the request, in the message body. There are usually extra headers to describe this message body, like Content-Type: and Content-Length:.

- The request URI is not a resource to retrieve; it’s usually a program to handle the data you’re sending.

- The HTTP response is normally program output, not a static file.

The most common use of POST, by far, is to submit HTML form data to CGI scripts. In this case, the Content-Type: header is usually application/x-www-form-urlencoded, and the Content-Length: header gives the length of the URL-encoded form data. The CGI script receives the message body through STDIN, and decodes it. Here’s a typical form submission, using POST:

POST /path/script.cgi HTTP/1.0

From: frog@jmarshall.com

User-Agent: HTTPTool/1.0

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 32

You can use a POST request to send whatever data you want, not just form submissions. Just make sure the sender and the receiving program agree on the format.

The GET method can also be used to submit forms. The form data is URL-encoded and appended to the request URI.

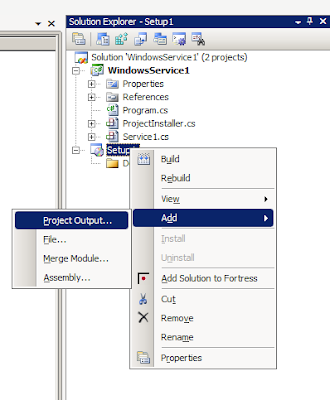

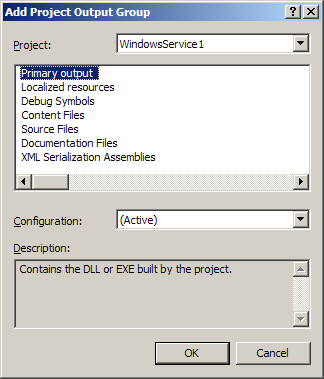

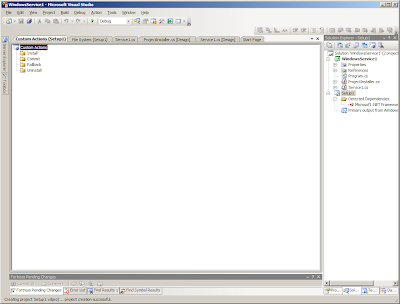

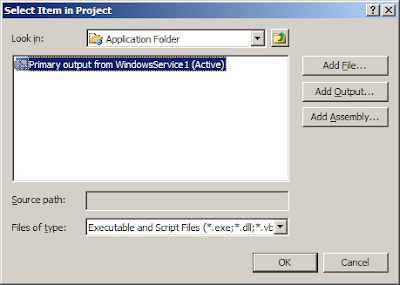

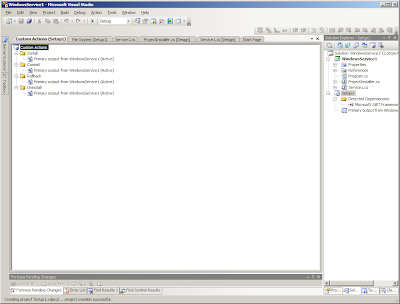

installing this service.

installing this service.